Stress, burnout strains education system nationally, locally

District, school fight to avert crisis as nationwide teacher shortage increases

December 17, 2021

There are fewer people choosing teaching as a career and there are more educators leaving the field. Effects of the higher workload for those remaining are becoming apparent and causing burnout. It’s a nation-wide problem that has been brought to the forefront since the pandemic started.

According to a study done by MissionSquare Institute, 52% of kindergarten through 12th grade employees feel stressed or burned out.

Many teachers at Bryan High are also feeling the burn out. In a survey given to all Bryan High staff, 50 responded, of which 42 were teachers. This represents 23% of the 215 person staff. The survey found 76% of respondents reported feeling stressed or burned out.

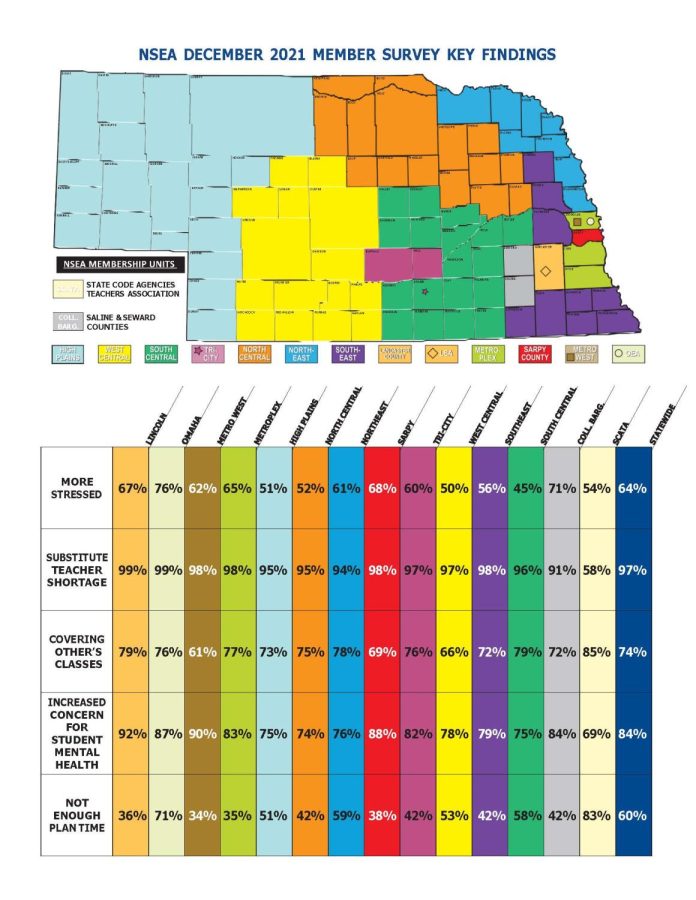

The Nebraska State Education Association (NSEA) identified both recruitment and retention problems of educators in a survey sent out to its members last month. Educators reported more stress and less time to plan than in previous years. Additionally, the Nebraska college system reported a 50% drop in enrollment in the education field over the last decade.

“The social, emotional and academic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic is growing worse by the day,” NSEA President Jenni Benson said. “Staff shortages and quarantines have stretched teachers thin to the breaking point. In addition to their own classes, teachers are covering classes for teachers who are ill or quarantining. They are losing their plan time, their time for one-on-one instruction with students, time to collaborate with their colleagues, and time to talk with parents. And this is the second year of these challenges – everything is compounded.”

NSEA is currently calling on state lawmakers to increase salaries for public education employees and is requesting to use $50 million of the state’s COVID relief funds for a $1000 stipend for their extra work.

Omaha Public Schools’ human resources team reported last month the district is currently about 93% staffed with most of the vacancies being in support staff roles such as paras and nutrition service workers.

“Staff shortages in education is a decades-long challenge that has more recently come to our area, heightened by the pandemic like every industry,” OPS spokeswoman Bridget Blevins said. “Omaha Public Schools has taken numerous steps to thoughtfully address these challenges in a variety of ways.”

Some steps OPS has taken are modifying the calendar to allow for more teacher workdays and hiring students in support roles such as interpreters and summer interns at elementary schools. Additionally, they recently launched a concierge program that would assist in non-instructional roles such as assisting cafeteria and transportation staff. Long term, OPS is investing in its para to teacher pipeline and its teaching academies that will be implemented at all its high schools.

However, Bryan High is almost fully staffed with only two vacant teaching positions, one in the English department and one in JROTC. Both positions are filled by long term subs.

“Our goal is to have a highly qualified and certified teacher in every classroom at,” Bryan principal Rony Ortega said. “When this hasn’t been possible, we have secured long term substitutes who have a strong background in education and know our Bryan High community.”

According to a study by RAND Corporation, since March 2020, over half of respondents cited the pandemic and stress from it as their main reason for leaving the profession. The second reason was lack of pay. In an anonymous survey conducted of Bryan High staff members, the stressors indicated by RAND Corporation are on their minds too.

“It’s [The Pandemic] been pretty awful, but it’s shown a lot of people that you need to be happy in life and not just work for the sake of work, there are other options out there,” a Bryan teacher who wished to remain anonymous said.

They also agree that teacher pay is too low. 88% of the Bryan High staff who responded to the survey reported they felt underpaid for the work they do.

“Teachers don’t become educators for the money, but we’d like to be compensated for the actual work we do,” one Bryan teacher said. “We don’t just teach a subject. We become parents, counselors, aides, we embody a whole system of support that takes a toll on us individually.”

Others have said additional responsibilities outside the scope of their contract are contributing to their stress.

“It feels like society is dumping large scale social failures onto the backs of teachers and then expecting us to make up for those larger failures,” a Bryan teacher said. “As teachers are expected to do more with less, we will leave the profession.”

While national studies have shown the crisis in education, OPS has been consistent in their number on resignations and retirements over the past three years.

According to Blevins, the district reported 289 resignations in the 2018-19 school year, 239 in the 2020-21 school year, and 320 in the 2020-21 school year, which is about a 4% resignation rate over the last three years.

In comparison, Bryan High resignation rate was slightly higher than the district’s with 5% but followed OPS’s trend with 12 resignations during the 2018-19 school year, 6 in the 2019-20 school year and 15 in the 2020-21 school year, according to head secretary Nanette Varley. Nationally, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported over a million teachers resigning since 2019.

Of the 42 teachers surveyed, only three plan to leave at the end of the year. While some are still undecided, majority of teachers plan on returning and many of their reasons were similar to art teacher Rebekah Pilypaitis’s;

“I’m staying because I love what I do and I love our students,” she said.

Bryan administrators have been actively trying to combat the national issue of low teacher pay. They have implemented different incentives and activities to promote higher morale, such as having more staff celebrations and more staff recognition like staff member of the week and month.

“I think they’re doing a really nice job of trying to increase morale around the building,” English teacher Jill Stephenson said. “They’ve had get-togethers and parties, and they’ve been supportive in lots of other ways.”

Retaining current teachers and making them feel at home is Ortega’s goal amid the national cry for changes in education.

“We continue to work hard to create positive climate and culture where staff want to work and where substitute teachers enjoy coming to work,” Ortega said. “We know that our current staff are our best recruiters, and what they say about our school can help recruit other teachers here.”

KAREN KILGARIN • Jan 5, 2022 at 12:10 pm

Well-researched and well written news article!